Mitú, By Liliana Michelena

Photos: Tomas Neira Villa

Nohora Janet Trujillo Ramos had never made spaghetti before. One evening after work in Mitú, a town of 15,000 in Colombia's Vaupés department near the Brazilian border, she did what millions of people do when they don't know how to cook something: She pulled out her phone and searched YouTube for a tutorial.

Boil water, add salt, cook for ten minutes. Simple enough. She made it her own way, adding plantain and cheese. Her four sons loved it.

Before this year, that wouldn't have been possible.

Nohora (pronounced Nor-uh), 36, works in territorial health governance for an NGO. A member of the Tucano indigenous community, she grew up in Tamacuarí, a hamlet deeper in the rainforest, and studied public administration while raising her children. But until she started her current job, she'd never had reliable, daily Internet access–just intermittent phone service that worked in some spots for a few hours before cutting out.

Now, the same device that teaches her new recipes lets her video call her aunt in Brazil, follow international news, and research for work. Internet arrived late to rural Vaupés, and it changed how she communicates, works, and even what she cooks for dinner.

Growing up in Tamacuarí, information traveled slowly. When Nohora's father lived in her birth community, news arrived through visitors, or letters carried by people traveling between communities. She remembers learning about the wider world in school, where a nun told students they could one day use the Internet to see places like the Vatican. "We didn't even know what life was like in a city context," Nohora says.

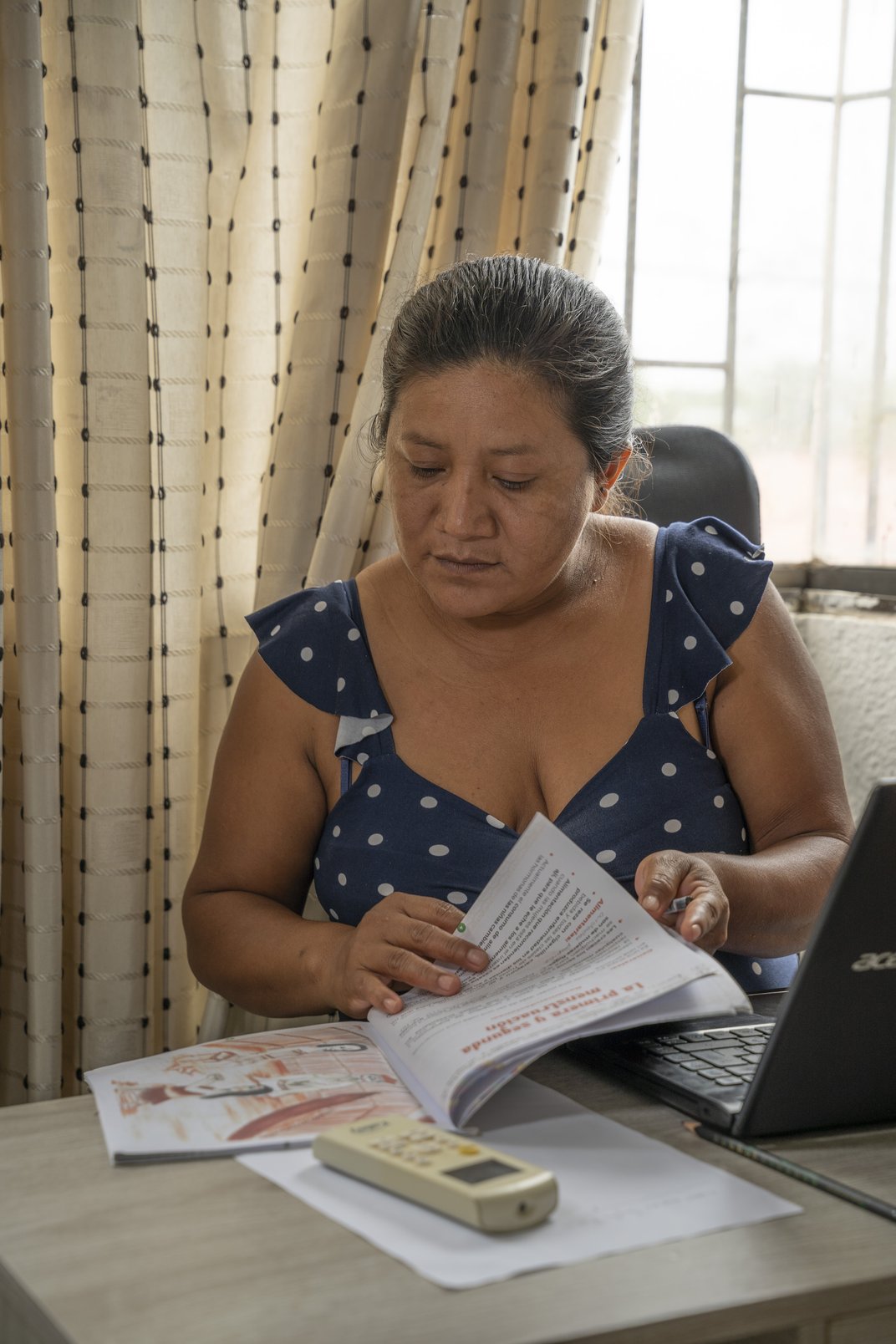

She got her first cell phone in 2010, but it was mostly useful for calls and text messages. When she started studying public administration in 2018, she finally needed the Internet for her coursework. "I came from a community where I'd never seen a computer, never manipulated a computer," she says. Her younger brother, who'd learned to navigate online, taught her how to search and find information.

The first thing she looked up? The philosophers she was studying in class. "In the books, the information wasn't complete, not all the details," she explains. Online, she could find where they were born, what they did in their lives, everything broken down in detail. The books her school used were old and outdated. The contrast was striking.

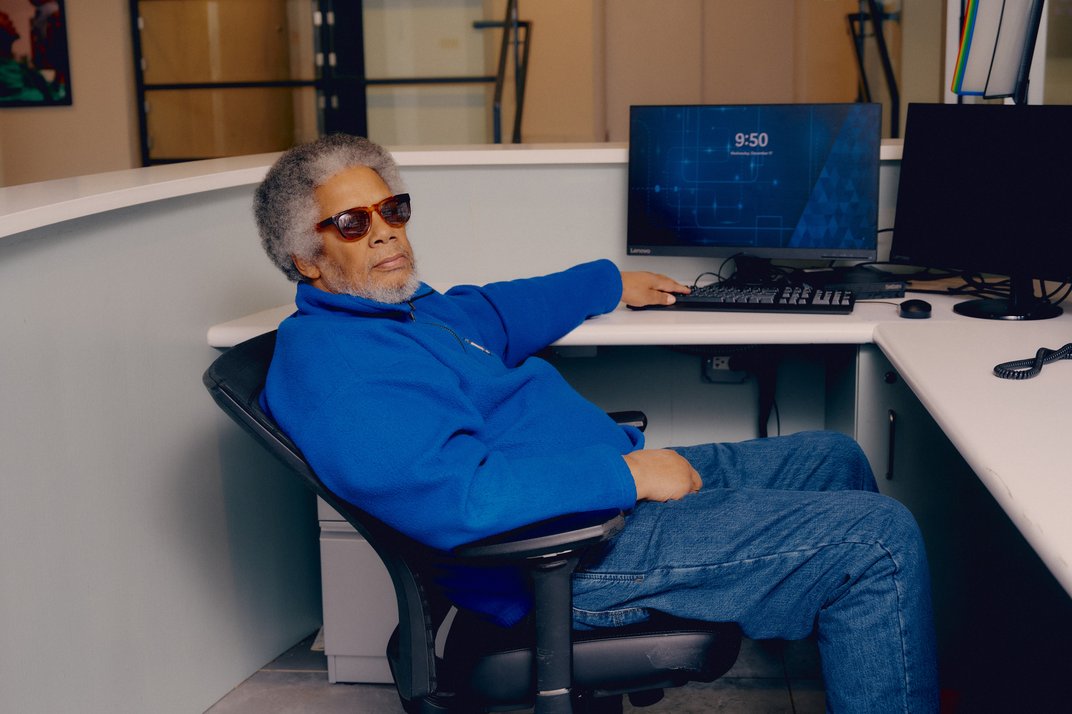

These days, Nohora spends most of her workday online. Her organization uses Google Drive for everything, so she's constantly connected. At home, she's set strict rules: No phones during meals, and her sons have scheduled times for their devices—homework first, then soccer practice, then limited screen time.

The Internet reshaped daily life across Vaupés. The department installed wifi zones and satellite antennas in strategic locations starting in 2023. Many communities now have connectivity at their schools. Her own father got a cell phone just three months ago.

This year, Nohora has taken online courses in leadership to strengthen her professional skills. She reads about international conflicts—Ukraine, Gaza, U.S. politics—thinking about how global events might affect her region. She's learned to make not just spaghetti but arepas with cheese, yuca dishes, empanadas with plantains. When her eight-year-old niece came to stay with her, Nohora had to look up something entirely new: How to style a little girl's hair. "I’d only ever raised boys!" she laughs. YouTube came through again.

Her oldest son, 19, is studying environmental engineering in Medellín, an urban center worlds away from Mitú. They video call regularly. Her aunt in Brazil, her cousins in Manaus—they're all a message away. "Before, you'd find out about things much later," she says. "Now I can know what's happening in my community, how my uncles are doing, what ceremonies they're planning."

Nohora isn't naive about the downsides. She worries about her younger sons spending too much time on their phones at night. "I feel like I did them harm," she admits, "because I gave them access, and now they're going to suffer consequences with their vision."

She's seen broader problems too. In some communities, families spend more time watching movies than fishing or tending their gardens. Child malnutrition has increased. "If they said, okay, there's an opportunity to study virtually, great, let's pay for it, let's get the kids enrolled—that would be wonderful," she says. "But there's no clear plan for how to use it."

She herself lost money in an online pyramid scheme. It was a hard lesson. Still, she believes the benefits outweigh the risks if people use it thoughtfully. Internet access has helped her advance professionally, stay connected across borders, and learn new skills. For indigenous communities, she thinks it could be a tool for territorial defense and strengthening autonomy—if used with intention.

"From the moment we use the Internet well," she says, "it empowers indigenous peoples, families, communities. But if we're just watching soap operas and playing games without basic knowledge of good use, that's a big disadvantage."