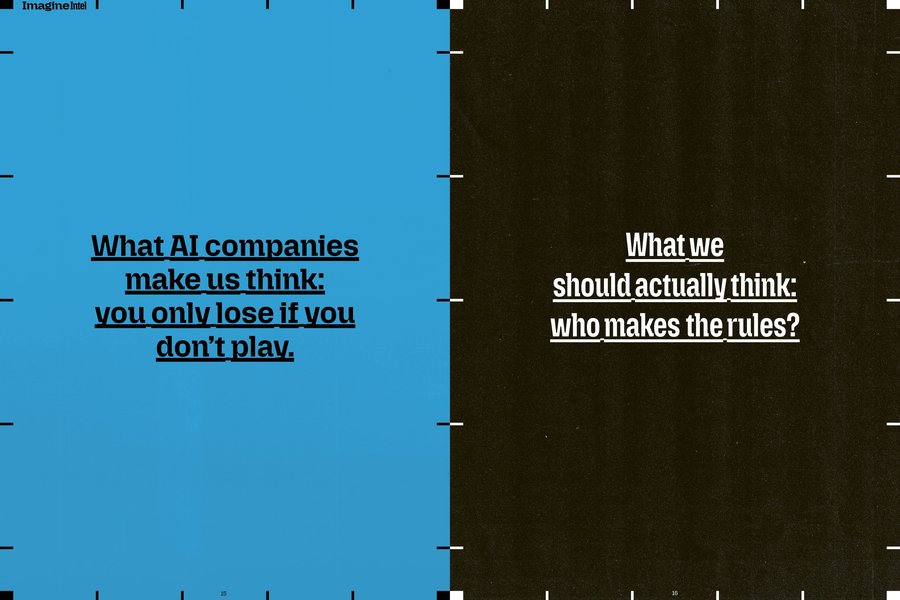

An excerpt from Imagine Intel: Creative Purpose at the Dawn of AI, our new zine capturing the hopes, anxieties, and demands of creatives working at a transformational moment for creativity and technology. Download the full zine below.

What is Creative Purpose in the Age of AI?

Many believe the modern Western concept of the artist emerged in the late 18th century, fundamentally transforming what an artist is, does, and their role in society.

Before this shift, artists were primarily seen as skilled craftspeople. Their role was largely utilitarian and decorative, bound by tradition and the expectations of those who paid for their labor. But shaped by the Enlightenment's emphasis on science and reason, and further accelerated by the industrial revolution where mass production became the norm, the artist's identity underwent a radical redefinition. No longer required to spend thousands of hours mastering a craft within rigid guild structures, the artist emerged as an autonomous creative individual—a genius figure who expressed personal vision and originality rather than executing someone else's specifications.

The artist was now expected to innovate, to break free from established rules and past traditions, to create for art's sake rather than purely for function or patronage.

The same narrative plays out today. A recent post on Adobe’s blog offers creative professionals “a pathway to growing their careers by freeing up time to do more of the things only they can do.” It is, indeed, a tale as old as time: technology is supposed to free us from constraints, democratize access and give us more time to do the things we really want to do. But the reality isn’t that simple. Every day, news headlines and social media feeds announce that artists, art directors, designers, strategists, and many more will be replaced – or face reduced rates in light of recent and rapid advancements in AI.

Jevons Paradox is a term often applied to the supply and demand of AI and computational power. The term arrived in 1865 when English economist William Stanley Jevons noticed something peculiar about coal: the more efficiently heat could be generated, the more coal people burned. The same metaphor applies to AI as technical leaps in efficiency rapidly drive down the cost per calculation. Yet, instead of using less energy, the use cases for computation increase and so does AI’s consumption of resources.

The same logic seems to apply to human labor.

From writer Tina He:

"Traditional economics might predict that AI-boosted productivity would reduce working hours, a four-day weekend for tasks that once took five days. But reality has different plans. [...] Productivity doesn't eliminate work; it transforms it, multiplies it, elevates its complexity. The time saved becomes time reinvested, often with compound interest."

It’s only natural then that values such as productivity, efficiency and speed are promoted as the key benefits of the big AI companies that want us to use their models. For example, one of the slogans of Claude’s 2024 marketing campaign is “A jetpack for your thoughts”, or a main chapter of Perplexity AI’s 2025 playbook, Perplexity at Work, is titled, Scale Yourself. This is a helpful approach if you’re a copywriter tasked with the job of creating hundreds of ads every day; a content creator trying to beat the algorithm; an illustrator working multiple jobs at the same time because the bills need to be paid; or another creative worker who finds themselves creating work under ever-increasing demands for speed, efficiency and output.

This is the reality we live in.

But let’s not make the mistake of thinking this replaces the journey that makes art and creativity meaningful to us.

Last November, Rosalía released her new album Lux. Written and recorded in collaboration with the London Symphony Orchestra, the singer emphasized that she didn’t use any AI tools in its creation: “It’s all human” she explained in the New York Times Popcast, emphasizing that despite the extraordinary feat of singing in 13 languages, she accomplished this through traditional human effort – years of study, collaboration with language experts, and countless takes to get the pronunciations and meanings right.

There might be many reasons why Rosalía’s album was so well received – breaking the record for most streamed album in one day by any Spanish-language artist, with 42 million listens on its day of release. But one of them is the specific moment in time where many of us fear that the rapid advancement of AI threatens to take away our humanity. To see Rosalía counter that narrative, spending years perfecting an album – which, in itself has become an almost lost art form due to the algorithmic re-structuring of the listening experience – and committing to the craft. The struggle, pain, failure, vulnerability, and ultimately pride of creating a work of art feels like an act of resistance.

You can argue that the ability to commit yourself in that way, have the time and resources available to do so, and find commercial success with it, is a luxury. Working in the creative industries, many of us have learned to live with compromise, distinguishing between creative work that’s aimed at a certain goal – to sell something – and the creative work we do for ourselves, or within more independent realms – where commercial viability isn’t the only metric of success. And yet, Rosalía remains inspiring: To take the risk to create on your own terms, follow your own path, and do it in whatever way you want is something we can all apply to our own practices.

The Artist in the Age of AI

Most artists today are navigating hybrid roles, where they increasingly need to know how to filter and shape culture rather than just creation itself.

To be an artist, much like online identity itself, is a cobbling together of multiple artistic expressions, which requires chameleonic levels of versatility. You’re an art director and a photographer and a designer; a thinkfluencer and a DJ and a part-time model.

So, what does it mean to be authentic in an age of AI? As many participants of the Imaginative Intelligence Assemblies pointed out, artists are no longer just makers. They are increasingly system designers, navigating tools, platforms, and audiences to shape meaning in a rapidly changing creative economy.

One thing that remains constant, and uniquely human, is taste.

In what has become the go-to term for describing anything from a form of critical judgement to the discernment of quality, taste within the context of AI is often mentioned as the thing that AI lacks: cultural context, emotional depth, and lived experience that define who we are as individuals; which then, when turned into prompts, supposedly generates what is distinctly unique on the other end.

Sari Azout, the founder of personal intelligence tool Sublime, puts it this way:

“AI is powerful but taste-blind. It can make anything but it has no idea what's actually worth making. But AI + your taste? That's the game-changer. The more AI can execute, the more your eye for what's interesting – your ability to discern and curate what matters and why – becomes everything.”

This approach reflects how many Gen Z creators already approach creative work. Having grown up with access to tutorials on YouTube and Skillshare, as well as easy-to-access software and hardware, newer generations of creatives are primed for versatility. Previously hard-defined roles and crafts like photographers, filmmakers, directors have already merged into the role of the multi-hyphenate creator: creatives that don’t fetishize any one tool or craft, are mostly self-taught and fluently switch between disciplines.

One such example of this growing multimedia, multiplatform expression is the director Harmony Korine, whose future design studio EDGLRD is expanding the horizons of older formats such as filmmaking and video games using machine learning tools. No longer satisfied with the traditional boundaries of filmmaking, Korine uses the term ‘blinx’ as a catch-all term for media: “Instead of films or games, a lot of these things – we’re just calling them blinx,” he says. Using advanced technologies to break away from past traditions, EDGLRD is but one example of the way artists are adapting to the changing digital environment.

The main takeaway is that new creative tools call for new mediums to explore what’s possible. And, since AI can only make predictions about the present based on what’s already happened, it’s up to us humans to predict what comes next.

Illustration by Dakarai Akil